This report was compiled by Joseph Eyre. You can find Joseph on Twitter here.

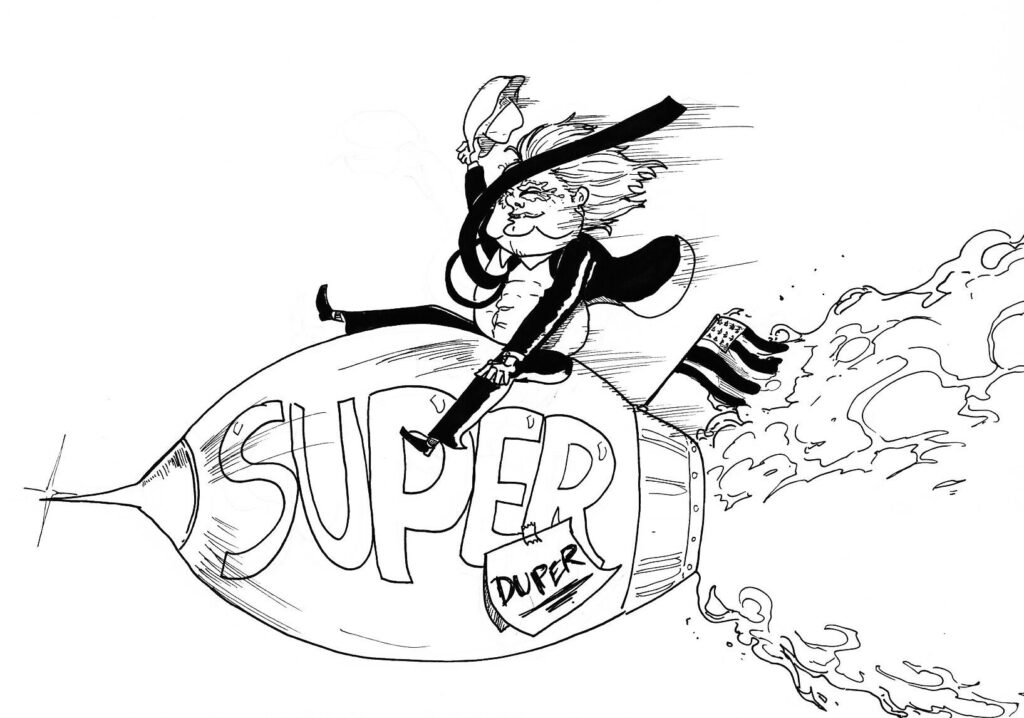

“I call it the super-duper missile,” bragged Trump in May at a White House ceremony for the unveiling of the United States Space Force’s new flag. As Chief Pentagon spokesman Jonathan Hoffman has confirmed, Trump was referring to a hypersonic missile currently under development by Lockheed Martin. In typical Trump language, the president has provided further confirmation of an escalating arms race in which Russia, China, the US and others now find themselves – and not without reason. Hypersonic weapons have the potential to be extremely destabilising; they could undermine nuclear deterrence, blur the lines of established military tactical dominance, and usher in a new era of warfare.

There’s an important context to the US’ appetite for the next generation of weaponry. In December 2019, Russia confirmed that it’s Avangard hypersonic weapons system had entered deployment, making it the first nation known to deploy such a weapon. The Avangard is a hypersonic glide vehicle, which is mounted on an ICBM and can carry conventional or nuclear weapons. Allegedly reaching speeds of up to Mach 27, the vehicle is capable of high speed evasive maneuvers in-flight which, according to Vladimir Putin, makes it “invulnerable” to any “existing and potential” missile defence systems.

While arms control expert Jeffrey Lewis has questioned these claims, speakers at a Missile Defence Conference last year acknowledged that the task of tracking and intercepting missiles, at least by existing defence systems, is now severely complicated. The conference report states that “the task of calculating the trajectory of a ballistic missile following a parabolic arc at speed is an already complex one, rendered nearly impossible by hypersonic glide vehicles that do not follow a standard arc of trajectory.” Likewise, at a 2018 Senate nomination hearing for the now-current Undersecretary of Defence for Research and Engineering, Michael Griffin stated that “we do not have defences against those systems.”

An illustrative example of the destabilising potential of rapid advances in missile technology, and their subsequent deployment, can be found in a similar development: the deployment of the Soviet intermediate-range SS-20 Saber in 1976. Unlike predecessor intermediate-range systems, the SS-20 could carry 3 warheads and with much greater accuracy. Likewise, its use of solid fuel and a road-mobile launcher meant that it could avoid detection, be launched at much shorter notice and from any road-accessible location, with an estimated flight time of 15 minutes. These new developments presented a much more significant threat than the intermediate-range systems which preceded it.

While you’re here…

Why not take a moment to subscribe to The International’s free monthly newsletter? It takes seconds to sign up, and you’ll stay up to date with the stories shaping our world at a pace that won’t overwhelm.

By virtue of its shorter range, however, the new missile disproportionately threatened Europe rather than the NATO alliance as a whole. The US did not initially consider the SS-20 to be especially threatening, and its agreement to NATO’s “Double Track” decision came primarily in order to ease concerns in Europe. The “Double Track” approach consisted of negotiations, with a view to limiting intermediate-range weapons, whilst also controversially deploying equivalent American Pershing II missiles. Although the initial deployment marked a substantial increase in tensions and a deterioration in East-West relations, this approach eventually culminated in the INF (Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces) Treaty, signed in December 1987. The treaty was the first time the superpowers had agreed to a reduction in their nuclear arsenals, and it led to the elimination of an entire category of nuclear weapon as well as the destruction of 2,692 missiles. NATO solidarity was an instrumental factor in finalising the treaty; had the US not responded to the concerns raised by Europe, and had European member states not agreed to host US Pershing missiles, the treaty would have been unlikely and future solidarity would have been jeopardised.

Present Instability

Unfortunately, in August 2019 the United States withdrew from the INF Treaty, blaming Russia. With NATO experiencing its’ “brain death”, according to Macron, and with the possibility of a much more isolationist President serving a second term in the White House, we may not see such solidarity in the near future. A disproportionate threat to Europe from now-permitted intermediate-range and hypersonic missiles, along with a resurgent Russia, may well be a further point of tension within the NATO alliance.

Europe is not the only region that faces destabilisation as a result of this new technology. Japan and India are both developing hypersonic weapons of their own, whilst China’s DZ-ZF is most likely in the early stages of operational capability, given its appearance in a 2019 military parade. Like Avangard, the DZ-ZF is a hypersonic glide vehicle. However, unlike the Avangard, the DZ-ZF is mounted on a purpose-designed DF-17 missile, which has a maximum range of between only 1,800 and 2,500km. This suggests a shorter range and conventional, rather than nuclear, application which is further supported by the Chinese Military’s confirmation that an anti-ship variant is in development.

Deployment of these missiles could have severe ramifications. With tensions increasing over competing territorial claims in the South China Sea, and a renewed threat of forceful China-Taiwan unification, the region has several potential conflict flashpoints. Given the vital importance of aircraft carriers in US power projection, and the central role they would play in any conflict, China’s ability to effectively strike even one would significantly alter the balance of power in the region.

The New Arms Race

The Centre for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments has confirmed that hypersonic weapons could indeed lower or negate the effectiveness of US carrier air defences. Furthermore, during the Chief of Naval Operations’ senate nomination hearing in 2019, Sen. Angus King (I-Maine) warned that “every aircraft carrier that we own can disappear in a coordinated attack. And it is a matter of minutes.” Given that a Nimitz class carrier has a crew of over 6,000, the loss of a single carrier could entail greater US losses than those recorded in Iraq and Afghanistan combined.

Trump’s boast is the latest sign that the US is now keenly aware of their technological disadvantage in hypersonics and they are now devoting significant resources to closing the gap (although deployment of their own versions will most likely increase tensions further). However, with current three-way arms-control talks between Russia, China and the US looking unlikely, and with an increasingly disunited NATO, an INF-style treaty limiting or banning these weapons seems a distant probability. For now, we are likely in the early stages of what will be an arms race to match those during the height of the Cold War.

Joseph Eyre is a staff writer for The International. You can find Joseph on Twitter here.