By Joseph Eyre

At the beginning of July, first minister Nicola Sturgeon and prime minister Boris Johnson engaged in a very public disagreement over whether or not there is a border between Scotland and England.

Trivial though it may seem, this is just one of the many issues resulting from an increasingly disunited Union built on convoluted and uneven constitutional arrangements. Heightened nationalism, Brexit, and now the Covid-19 pandemic are highlighting what many view as inherent weaknesses in the UK’s constitution and furthering calls for significant reform. However, from the reversal of devolution to federalism, Scottish independence and even the dissolution of the Union, reform means radically different things to those across the political spectrum. Regardless of the outcome, the status quo is unlikely to last.

To mark one year since becoming Prime Minister, Boris Johnson embarked on a trip to Scotland. Whilst there, he praised the “sheer might” of the Union and spelled out the “disaster” which Covid-19 would have been in an independent Scotland. Nicola Sturgeon, on the other hand, has been quick to point out that Boris Johnson’s visit further strengthens the case for Scottish independence, given that they’re governed by “politicians we didn’t vote for.” The visit, and subsequent tensions, are unsurprising given recent polling showing unprecedented support for Scottish independence; a Panelbase poll from June has the ‘Yes’ vote for independence leading at 50%, with ‘No’ at 43%.

While You’re Here

Why not take a moment to subscribe to The International’s free monthly newsletter? It takes seconds to sign up, and you’ll stay up to date with the stories shaping our world at a pace that won’t overwhelm.

The Covid-19 pandemic and a renewed focus on Brexit negotiations have thrown the constitutional stand-off between London and the devolved governments into the limelight. Differing messaging and enforcement of lockdowns between all nations of the UK have left many more aware than ever of a lack of unity and coherence. While England has generally eased restrictions earlier, the other nations have adopted a slower, more cautious approach to coming out of lockdown, leading to significant confusion and differing health outcomes.

Likewise, as Brexit negotiations enter their critical phase and details of new trade deals emerge, tensions are increasing. Given the already problematic fact that of all four nations, only England and Wales voted to leave the EU, this was somewhat inevitable. However, proposed legislation has emerged which appears to allow Westminster to unilaterally determine food and environmental standards in the new UK internal market. Along with the familiar concerns of a ‘race to the bottom’ in regulation, Welsh and Scottish leaders have expressed concern and described the legislation as a “power grab.” The Scottish constitution secretary, Michael Russell, has vowed to fight the plans in “every possible way”, laying the foundations for one of the most significant constitutional disputes regarding devolved powers since they were first granted.

Devolution & the UK’s Constitution

Devolution of power to the UK’s constituent nations does not have a long history. Following a landslide victory in 1997, Tony Blair’s government set out to act upon their manifesto promise of devolved institutions for Scotland and Wales. Referendums were held in the two countries and both voted for the establishment of their respective legislatures. In a similar process, the Northern Ireland Assembly came to fruition as a result of the Good Friday Agreement and its accompanying referendum. By 1998, all three nations had their own legislative bodies, albeit with differing levels of autonomy, and their executive branches followed shortly thereafter (the Scottish Government and Northern Ireland Executive were established in 1999, and the Welsh Government came in 2006).

The UK’s constitution, by contrast, has a history of unprecedented length. Unlike the majority of sovereign nations, the UK’s constitution is not a comprehensive, single document; it is made up of a mixture of hundreds of acts of parliament, court rulings and documented conventions. From Magna Carta in 1215, to the establishment of an independent Supreme Court in 2009, the UK’s constitution has been subject to significant and continuous change.

Given this inherent flexibility, it is entirely plausible, and probable, that the UK will undergo significant constitutional reform in the near future. Faced with increased support for Scottish independence, one such example of reform could be that the UK opts to become a federal nation. Both the Prime Minister and the Leader of the Opposition have previously expressed support for this as an alternative to the break-up of the Union.

A Federal UK

Broadly speaking, all states can be classified as either unitary or federal. In a unitary state, such as the UK in its current form, the central government is ultimately supreme. A federal state, on the other hand, is made up of several self-governing regions under a federal government, and the division of powers between them is usually constitutionally entrenched.

Although devolution has meant the UK has certainly become less centralised and unitary, devolved powers to the nations vary and are far from constitutionally entrenched. The proposed legislation mentioned above, concerning food & environmental standards is a clear example of that. A federal system would grant significantly more powers and autonomy to each nation, including England.

Despite the significance of such a radical change, there is currently no definitive blueprint for a federal UK. An early proponent, Winston Churchill, suggested home rule for the nations as well as for English regions, with each having their own parliament. More recently, Whitehall has allegedly shown an interest in a ‘City Regions’ model, whereby the twelve largest cities in England would have mayors and further devolved powers. This has, to an extent, already begun. The Manchester and Liverpool city regions gained mayors in 2015 and 2017, respectively, and the two recently cooperated in an attempt to encourage increased coordination between central and local government in dealing with ‘local lockdowns.’

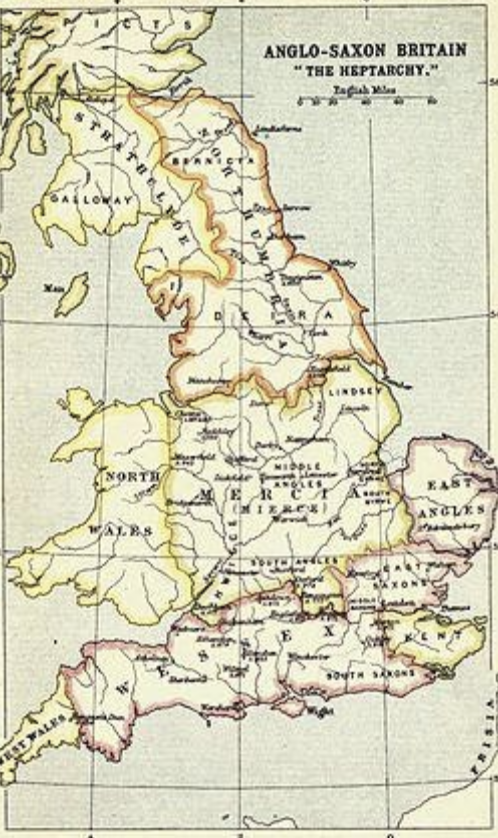

Another, more historic suggestion, is the creation of seven major states along the lines of the Anglo-Saxon Heptarchy (Wessex, Essex, Sussex, Northumbria, Mercia, Kent and East Anglia), with a few smaller states too. While probably too outdated to work in practice, it acknowledges the strong regional identities which exist in the regions of England and nations of the UK. A more statistically and demographically balanced option could be the establishment of states along the lines of the EU’s NUTS 1 statistical regions of the UK. Comprising 9 English regions as well as Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, the regions are used by the EU and the Office for National Statistics and match the official, already-existing Regions of England.

Whilst there are clearly a wide range of options for a federal UK, it is an idea very much in-development. As support for Scottish independence continues to increase, we will likely see it increasingly proposed as an alternative option.

Long-overdue constitutional reform has been delayed by Brexit and Covid-19, but these crises have also strengthened the case for such reform. Support for it has undoubtedly increased, and some kind of revision to the country’s messy constitution seems inevitable. Whether as a result of Scottish independence, the adoption of federalism, or increased devolution, the future of the UK in its current form has arguably never looked more uncertain.

This report was compiled by Joseph Eyre. You can find Joseph on Twitter here.