By Jude Holmes

The UK just became the world’s largest open-air fat camp, with compulsory attendance. Certain foods will no longer be eligible for special offers, sugar taxes are being re-evaluated and tightened, and, from next year, your doctor will receive money for referring you to weight loss plans. While we wait for this initiative to kick in, there’s an app for that.

The spark igniting this flame is Boris Johnson, who struggled to “bounce back” after catching COVID back in March. Johnson blames his weight, and that sounds right doesn’t it? After all, we are consistently taught to count calories and watch our figures. Over the years we’ve seen “extra pounds” linked to various debilitating illnesses such as diabetes, lower life expectancy and general lack of health. Unfortunately for Boris, biology is never that simple and the latest research suggests that weight isn’t the worrying factor at all.

“Don’t know much Biology…”

Your weight number is made up of all that is physically you; blood, bones, organs, and tissues all parcelled up into a human. There is an average weight for these components, usually based on gender, and this is often scaled using the seemingly omnipresent BMI formula (weight/(height)^2). The inventor of this scale was a mathematician looking at population-wide statistics, and BMI has long been criticised for not meeting standards as a diagnostic tool for the individual, most notably as athletes are described as overweight for carrying significantly more muscle than the average human. If we are targeting individual weight loss, BMI is quite evidently not the correct tool to use. Yet many healthcare systems continue to use this measurement, contra to the scientific standard of changing a methodology in the face of new evidence. In fact, waist measurements and waist-to-hip ratios have been shown to be more accurate in determining propensity to certain diseases. However, waist-to-hip-ratio is predominantly genetic, so we begin to see how targeting the individual using a population data spread might be the wrong tactic. Around 70% of weight is genetically predisposed compared to 80% of our height, which we known can be affected by nutrition in early childhood.

Weight fluctuates with time, children often gain weight just before a growth spurt, the elderly lose bone mass, and hormonal diseases can cause weight loss or gain. Emotionally, however, we get caught up in the weight of one specific tissue: fat. The word itself is descriptive of a group of chemical compounds. In the human body, these compounds often provide functions of energy storage, insulation, and protection. Fat is either directly ingested or manufactured in the body from the food we eat. Without it, we die. Stats vary widely, but a top male athlete will carry around 10% body fat (female athletes generally carry more). We need some fat to survive, but are constantly told that too much will kill us. So how much fat should we have?

Be Rich, Not Poor

“Eat Less, Move More” has been the golden rule of weight loss for decades, but this is a gross oversimplification of the data. Studies show consistently that coming from a lower socioeconomic background, lack of sleep, stress and certain medications or illnesses all contribute to your propensity to gain weight. Studies that often show correlation between weight and disease assume in their conclusions that the weight caused the disease, not the other way around. Even the NHS agrees that weight change is sometimes a signal of an underlying condition. The government is not at all clear that it understands these distinctions in the current Covid-19 report.

Dr Katherine Flegal produced a meta-analysis (the gold standard of research) showing that people in the “overweight” BMI category are the best protected from death, compared to their “normal weight” conterparts. Another study showed that just eliminating fat using liposuction doesn’t improve standard health biomarkers.

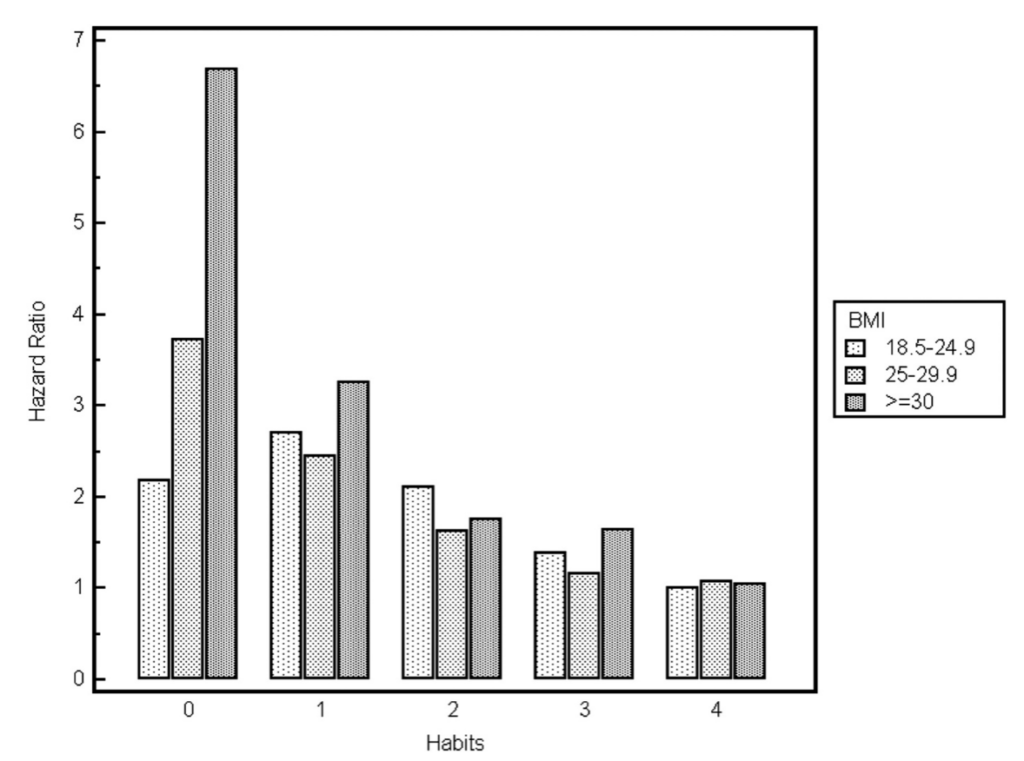

In the pictured graph from a third study, we see the Hazard Ratio (mortality) vs the habits of people in three different BMI categories of “normal”, “overweight” and “obese+”. Healthy habits were defined as not smoking, consuming 5 fruit and vegetables daily, regular exercise and a moderate alchol intake. As an obese person, by engaging in one of these habits, you effectively half your risk ratio to a similar rate as a lower weight category. We know that positive changes have been made through quit smoking campaigns and the This Girl Can campaign by Sport England encouraged 2.8 million women to increase their exercise, effectively moving us to the right-hand side of the graph.

Between 80-95% of diets fail, resulting in a “rebound” weight of the same or higher than start weight. Nutritionists are calling for more research to be done into measuring the stress on the body caused by weight cycling; if dieting for 20+ years puts extra stress on the body and increases weight gain, then dieting could be partly to blame for higher BMIs and a higher Hazard Ratio. Our evidence for diets “working” is often anecdotal, to assess if the story is truly worthy of the 5%, consider if the weight loss is over 15-20kgs (“normal” weight fluctuation) and if the loss was sustained for over 5 years.

Stigma Replacement Therapy

Far from being just ineffective, the “war on obesity” stigmatises fat people, feeding a false narrative that fat is disgusting, unhealthy, and immoral. This stigma is present even in the science that is intended to better our understanding. The research that shows extra fat deposits around vital organs in thin people is dangerous but calls these people “metabolically obese” instead of entertaining the idea that thin isn’t always better. Only 1.4% of trainee health professionals show a neutral or positive approach to overweight and obese people. This weight bias negatively affects both thin and fat people, compared to a Health At Every Size (HAES) model. You can test your own biases with Harvard’s ongoing study, Project Implict.

Asking people to “save the NHS” puts a deliberate onus on individuals for something that is often a class issue, defined by food deserts and stressful working and housing environments. Johnson’s £50 bike scheme isn’t a terrible idea, but it seems limited in scope when sports equipment and clothing often isn’t made for the people who the government is targeting; when fat people are accommodated, outcry occurs. It also seems unethical to tempt doctors with making a profit off their patients when the money could go directly to improving any of the actual problems that cause ill health. Promoting weight loss in this way is directly encouraging disordered eating, something of a pandemic in the UK, and an approach actively criticised by the Eating Disorder charity BEAT. It also reminds us that we must maintain health at all costs or face public ridicule in the stocks, so god forbid you have a long term illness or disability and raise your voice in this debate.

So what did we learn from all of this? Perhaps that Boris Johnson has bet on the wrong horse, and “the Science” disagrees with him. But “the Science” so often disagrees with itself, as there never was one correct answer to begin with. It is an ongoing debate, a discussion and argument, trying to piece together the best evidence we have to prove or discredit current theories in the continuing endeavour for human advancement. If the pandemic has taught us anything, it’s that politicians must be willing to update their policies in line with the changing theories, and explain their actions clearly to the public. The future of leadership will depend on it, but progress is slow.

Jude Holmes is a staff writer at The International. Find her here on LinkedIn.