It was the best of times, it was the worst of times. Almost to this day four years ago, Hong Kong’s police were dragging away the last protesters and tearing down the final remnants of what became known as the Umbrella Movement. The mass protests calling for democracy, symbolised by a yellow umbrella, spontaneously erupted after police fired teargas at demonstrators outside Hong Kong’s government complex. The crowd of mostly university students shielded themselves with umbrellas, and those images traveled around the world, showing a hitherto unseen face of Hong Kong.

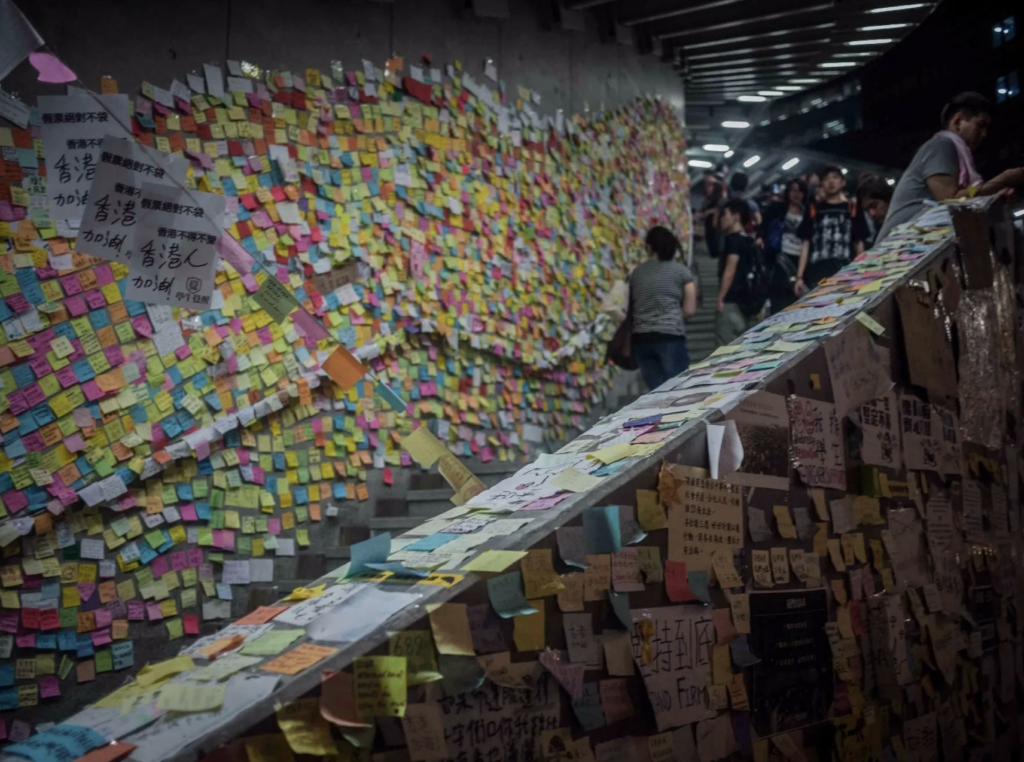

The demonstrations lasted 79 days. At its height, tens of thousands of people set up tents to turn one of Hong Kong’s major highways into a campsite. It made international news headlines daily, not only for the city’s struggle against China but also for its genteel nature. The protest site had makeshift tutorial halls for students missing out on lectures, it became the centre of a burgeoning art scene and a tourist attraction where photographers were welcomed warmly.

But It was also a signal to the Chinese government that there was a defiant side to Hong Kong which would not take decisions made on its behalf lightly. And since then, China has tightened its grip on the city.

Joshua Wong, one of the student leaders who spearheaded the movement tells The International he has no regrets. “It proved that Hong Kong is not just an international financial city, it is also a protest city, it shows how we are not just focusing on economic interest and financial market performance, we also fight for human rights and fight for the dignity of Hong Kong people”.

Wong has become the poster boy for the city’s struggle against Beijing’s authoritarian rule, with his story and fight for democracy having been made into a Netflix film, “The Teenager Versus the Superpower”.

Since the protests in 2014, it’s been a bruising few years for Hong Kong. Beijing has made several unprecedented moves to bring Hong Kong in line with other Chinese cities where human rights and freedom of expression are heavily restricted.

For those who are not familiar with this former British colony, in 1997 when the city was handed back to China there was an agreement that it would be governed with autonomy for the next 50 years. It would be what’s called a ‘Special Administrative Region’ of China. And unlike the rest of the country, it would have political freedoms, it would continue to enjoy press freedom and the right to protest, and there would be a process to eventually grant the city full democracy.

But in the past couple of years there have been developments which human rights observers describe as chilling. Democracy campaigners and protesters, including Joshua Wong and fellow student leaders of the Umbrella Movement, were jailed in 2017. Press freedom has come under attack, and electoral rules for the governing Legislative Council have been changed at will to favour those who support Beijing.

“The Chinese authorities probably believe that the previous soft approach towards Hong Kong has become ineffective, there was no more need to keep on adopting this method or to persuade the people to be patient, to wait till the conditions are right and to accept that the democratisation process should be gradual.” Political Analyst Joseph Cheng explains the abrupt change in Beijing’s tolerance towards dissent in Hong Kong.

“So in a way, the Occupation campaign (also known as the Umbrella Movement), represented a kind of crisis and subsequently the Chinese authorities adopted a much tougher line. That is to say there will be no negotiations on the issue of political reform”.

“[We are] letting the world know that under the greater influence and power of China, we stand in the frontline against the rising China model.”

Joshua Wong, Pro-Democracy activist

The pushback against Beijing isn’t purely about democracy. It’s about people in Hong Kong preserving a way of life and identity. Perhaps, a milder sense of nationalism now prevalent in many parts of the world.

University of Oxford-educated Gary Wong is the co-convener of the Path of Democracy, a local think-tank that is trying to find a middle ground and promote dialogue with Beijing in the pursuit of universal suffrage.

He says, “Not only after the umbrella movement in 2014, but also after Brexit, or after Donald Trump’s election, you can see the rise of identity politics is actually a worldwide phenomenon. But in Hong Kong I think especially people born after 1990, have strong identity as a Hong Kong-er. And in this case it’s not just about whether you are Chinese or from Hong Kong but it is also various values.”

For Twenty-two year old Joshua Wong it’s about preserving the basic human rights he grew up with, and realising a promise made to his generation: The right choose Hong Kong’s leader through popular vote.

“I am still optimistic of the people’s will”, he explains.

“Especially the youngsters, even though we may be a bit depressed, and a bit tired we still keep on fighting for democracy, and letting the world know that under the greater influence and power of China, we stand in the frontline against the rising China model.”

Divya Gopalan is an international correspondent and news anchor based in Hong Kong. She covered Hong Kong’s landmark protests in 2014 and the subsequent political developments for Al Jazeera English news channel. Her Twitter account can be found here.