At times, it can feel as though a large part of modern politics is two sides throwing buzzwords at each other until the tedium becomes too much to bear and we stop reading the news. Wrapping up complex issues in near-meaningless slogans is a global (and historical) phenomenon, be it ‘Get Brexit Done’ in the UK, ‘Build a Wall’ in the US, or even the (translated) ‘Now, There Will Be Justice’ of the Lok Sabha in the Indian General Election this year.

One catch-all phrase, however, has gone truly international. Reference to a ‘Green New Deal’ has appeared in parliamentary records in countries as diverse as Argentina, Australia, the UK, Sierra Leone, and the US among many others over the past year.

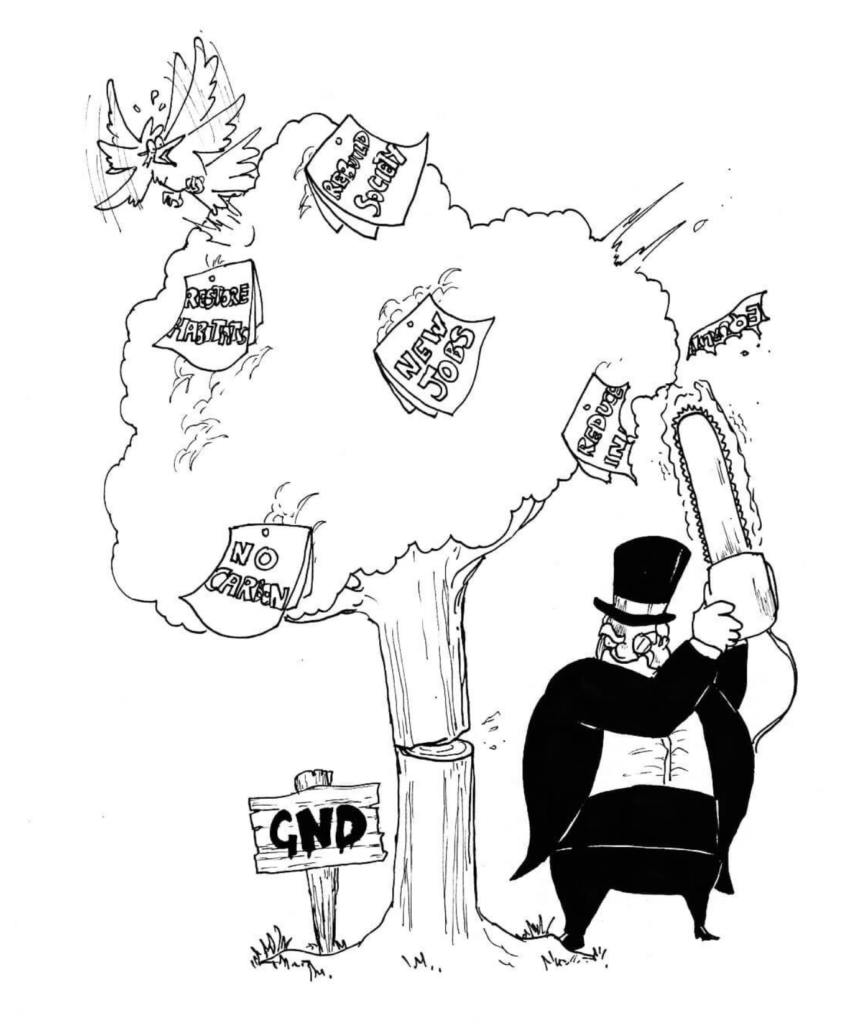

For its supporters, it’s a way of saving the planet from inevitable climate disaster. For its opponents, its another example of crazy left-wingers plotting to tax all your fun away.

But what does a Green New Deal actually mean?

To fully understand the term, we need to go back to 1933. In response to the Great Depression, President Franklin D. Roosevelt enacted a series of economic reforms. These were aimed at giving support specifically to farmers, the unemployed, young people, and senior citizens. His programme also included policies to regulate the banking industry, which was seen as partially responsible for causing the depression in the first place.

Fast-forward today, and politicians are arguing for the spirit of Roosevelt’s economic reforms to be reincarnated in a ‘Green New Deal’. In broad terms, it is an attempt to re-wire the economy in order to combat what the deal’s authors see as the two great challenges of the 21st Century – climate change and inequality.

If you’re interested in getting down into the nitty-gritty, you can read the copy of the bill that was submitted for a vote in the US senate right here. That document, however, provides a set of ambitious goals rather than a pathway to achieving them. It includes ideas such as establishing clean food, air, and water as a basic human right, bringing the US to net-zero carbon emissions by 2050 and overhauling the country’s transportation system by investing in electric vehicles and a higher standard of public transport.

Crucially, the bill does not include ideas such as ‘a ban on ice cream, cheeseburgers, and milkshakes’, as a Republican Senator suggested. However, the fact that the Green New Deal is so light on detail does present an opening for its opponents to fill in that detail for themselves.

An important distinction when reading about the Green New Deal is that it can mean different things in different contexts. In the US, it is likely to refer to the specific bill brought forward this year. Elsewhere, it can be used as an aspirational term for something that a government should be looking to do rather than a specific set of policy ideas.

And while that is the case, a Green New Deal is a very easy policy for politicians to publicly support. When it comes to the real work of drafting legislation, however, it’s an even easier one to ignore.