By Adam Bennett

“Within our mandate, the European Central Bank is ready to do whatever it takes to preserve the euro. And believe me, it will be enough.”

Mario Draghi, speaking as ECB President in 2012

With those words, the story goes, Mario Draghi set in motion a chain of events which rescued the euro. Not only that, but Greece – which many feared could crash out of the EU amidst a disastrous debt crisis – maintained its place not just in the Union but also within its single currency.

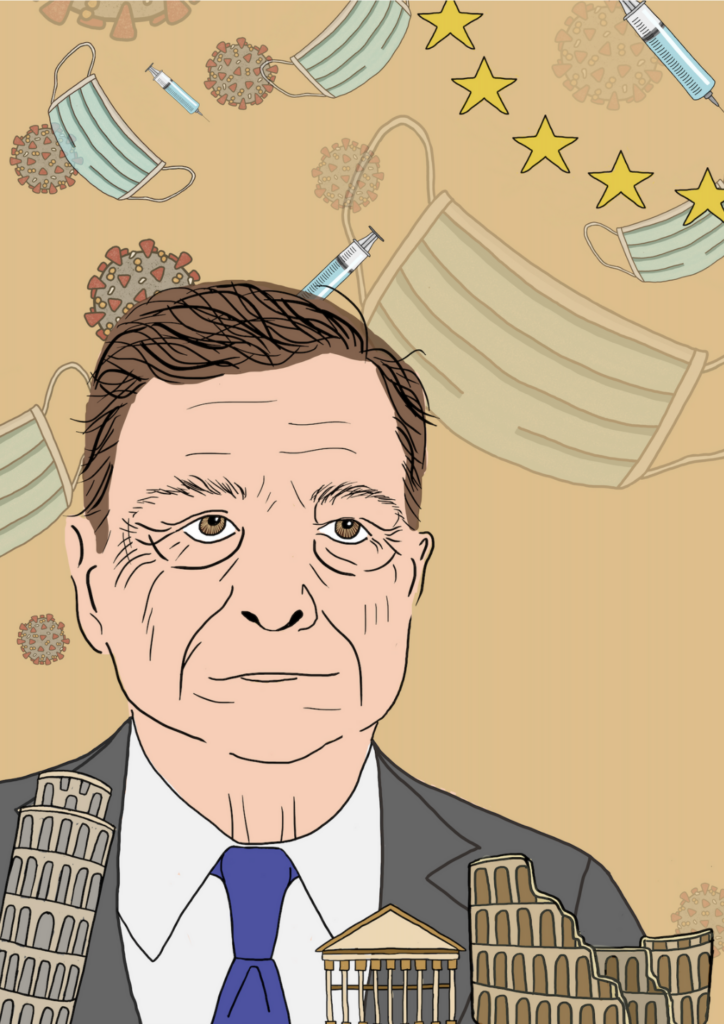

Draghi’s success won him a reputation as close to ‘rock star celebrity’ as anyone in the banking industry could feasibly get. His policies were also credited with a decline in borrowing costs for in-debt countries like his native Italy. In short, Mr Draghi seems to have the midas touch when it comes to diffusing complex crises.

And he’s going to need it again.

Now aged 73, earlier this year Mr Draghi received a call from the Italian President Sergio Mattarella. Following the resignation of Prime Minister Guissepe Conte, Italy needed a new leader. And Mr Draghi – affectionately nicknamed ‘Super Mario’ – answered the call.

His near-mythical reputation as a dedicated public servant and fixer will now be put to the test in the veritable snake pit of Italian politics. He faces the unenviable task of guiding his country through a pandemic and healing a toxic political culture, all whilst re-orienting an economy that was in steep decline long before Covid hit.

One Last Job

But how did we get here? Draghi, for all his fame, has never been a politician. Not one Italian voted for him to become the country’s new leader, and yet he was perhaps the only man in the world capable of commanding a majority within Italy’s tempestuous and fragmented parliament.

Around the start of this year Italy’s politics was, even by its own standards, in a state of utter chaos. A politically weak coalition government, bruised and battered by the pandemic and other more deeply-rooted issues, had just fallen apart. Matteo Renzi, once Italy’s Prime Minister himself, decided to bring down the fragile house of cards by withdrawing the support of his Italia Viva party from the government.

During the height of a grim pandemic winter, Renzi’s move was described by politicians of various parties as ‘reckless’, ‘a grave mistake’, and ‘an act against Italy’. Renzi, for his part, argued that his decision was taken as he could not support the government’s lukewarm plans for a post-Covid economic recovery. Whatever the reason, the result was anger and chaos.

It appeared for all the world as though Italy was going to be headed for another general election (potentially its second in three years). Pressing ahead with elections in the midst of a pandemic, however, was not a prospect that enthused Italians. Particularly given that, by the state of opinion polls, there was scant chance of a fresh parliament being able to achieve a clear political direction or even create a stable government. At an acute moment of crisis, Italy’s political leadership had fallen apart at the seams.

As the country’s President and head of state, the former lawyer Sergio Mattarella faced the unenviable task of conjuring a solution. However, utilising a dash of creative imagination and a dusty old book of contacts, he was able to do just that.

While You’re Here…

Why not take a moment to subscribe to The International’s free monthly newsletter? It takes seconds to sign up, and you’ll stay up to date with the stories shaping our world at a pace that won’t overwhelm.

Mario Draghi was supposed to be enjoying his retirement. The former banker had called time on his career whilst at the top of his game. At the end of his term leading the European Central Bank in 2019, Draghi was an admired figure throughout the governments of the European Union. He retained a strong friendship with the German Chancellor Angela Merkel, and even those who had never worked with him respected his reputation. In February of this year, however, Mattarella convinced Draghi to leverage that reputation as a means to heal Italy’s political divisions and avoid a potentially chaotic election. There was, argued Mattarella, simply no-one else capable.

And so, with Italy in the teeth of the most fraught and dangerous crisis in its modern history, Mario Draghi was back in the game. And the stakes had never been higher.

Navigating The Snake Pit

Around the time of Draghi’s swearing-in as Prime Minister, there was much fanfare. In the eyes of many onlookers, there was finally an adult in the room of Italian politics. Draghi’s mandate was undeniable – his leadership was approved in parliament with the second-largest majority in the history of the Italian republic. Even Matteo Renzi, the man who pulled the rug out from under the previous government, hailed Draghi’s leadership in an interview with the BBC. “Mario Draghi was the Italian who saved Europe”, suggested Renzi. “And now, I think he is the European who can save Italy”.

Draghi, for his part, has made a lot of the right noises. The former banker has waived his Prime Ministerial salary, for example, in a move to dispel the widespread notion that Italian politicians are ‘on the take’ (an Italian lawmaker’s salary is over double those in some comparable Western European countries).

And yet, any honeymoon period in such circumstances can not be expected to last. Did Italian MPs offer their support to Draghi because they were moved by his inspiring record of public service? Or did they do so because the currently whiter-than-white Prime Minister represents an ideal scapegoat to which the blame for upcoming difficultes can be pinned? A pragmatic analysis might well find that Draghi and Italian MPs are little more than allies of convenience.

Signs of unease are already starting to appear. The centre-left Democratic Party, which one might expect to be the EU-backed Draghi’s natural allies, has recently made moves to undermine the Prime Minister. Angling for a more progressive approach to the country’s economic recovery, the Democratic labour minister Andrea Orlando ambushed Draghi by announcing an extension to Italy’s pandemic-enforced ban on firing employees. Draghi had been seeking to ease the ban in order to lift financial pressure on employers, and Orlando’s stunt left the Prime Minister awkwardly apologising to unimpressed business leaders.

Further to that, the Democrats have also recently proposed a 10,000 euro stimulus package for each and every 18 year-old in a bid to reignite spending and investment. This would be paid for by higher taxes on the rich. Draghi’s response was cold – “now is not the time to take more money away from people. Now is the time to give it back”.

At the time of writing, Italy is set to be the beneficiary of 200 billion euros in the form of grants and loans from the EU, as part of the bloc’s pandemic recovery fund. Such an eye-watering amount of capital, the largest economic stimulus in Italy’s history, is destined to be fiercely and passionately argued over by the country’s MPs.

The challenge for Draghi, then, is in keeping it all together until Italy’s next scheduled elections in 2023. After a distinguished career in banking and economics, there is an oddly comic-book feel to Draghi’s character now. Having rescued the Eurozone, he retired as a hero. Now, he risks governing long enough to become a villain.

Adam Bennett is the editor-in-chief of The International. You can find him on Twitter here.